Cambridge, MA.

2023

2023

«Hymn to Ninkasi»

Next ︎︎︎

Avisors:

Francesca Benedetto

Institution:

Harvard GSD

Team:

Rosita Palladino,

Yimei Hu

Francesca Benedetto

Institution:

Harvard GSD

Team:

Rosita Palladino,

Yimei Hu

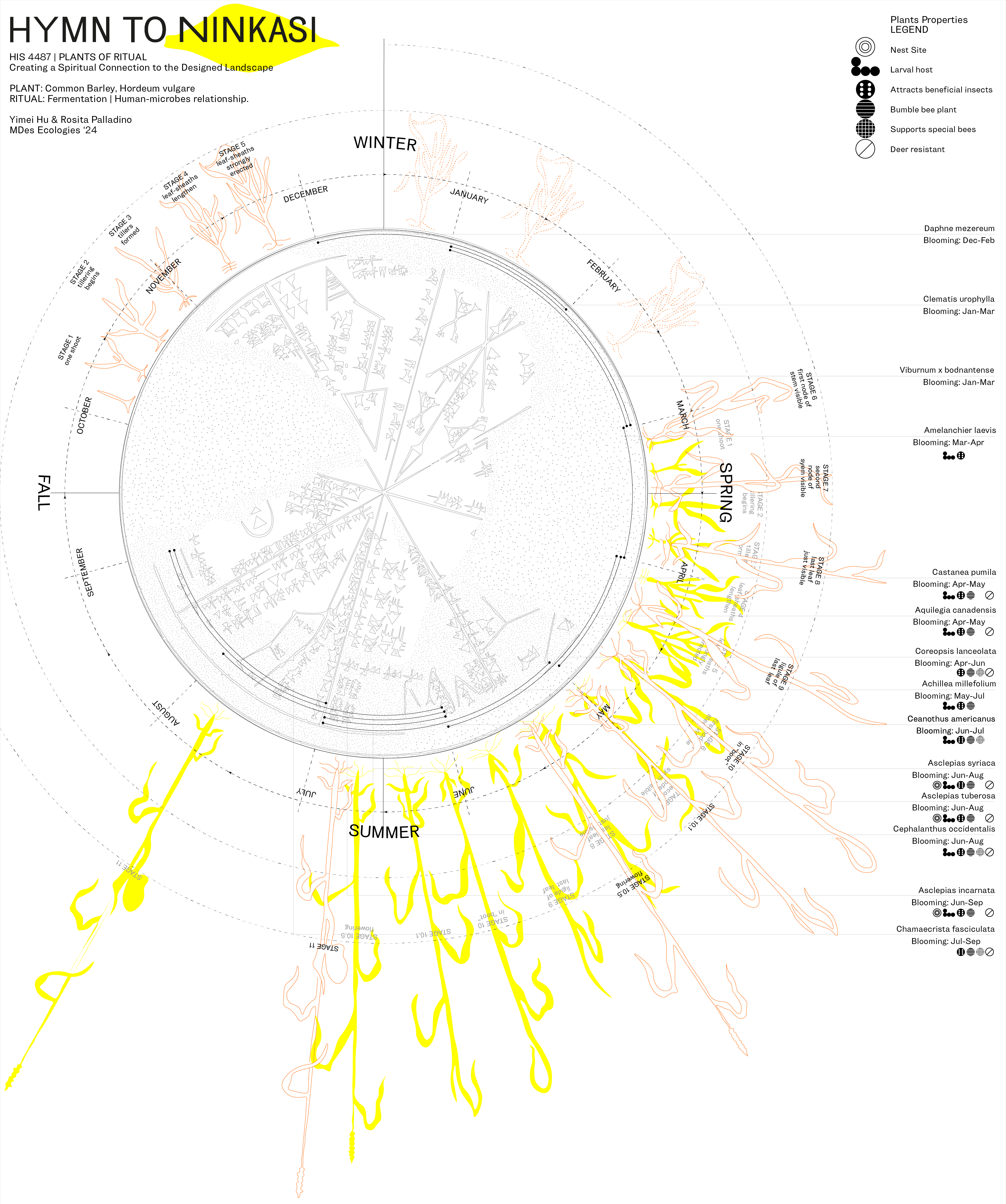

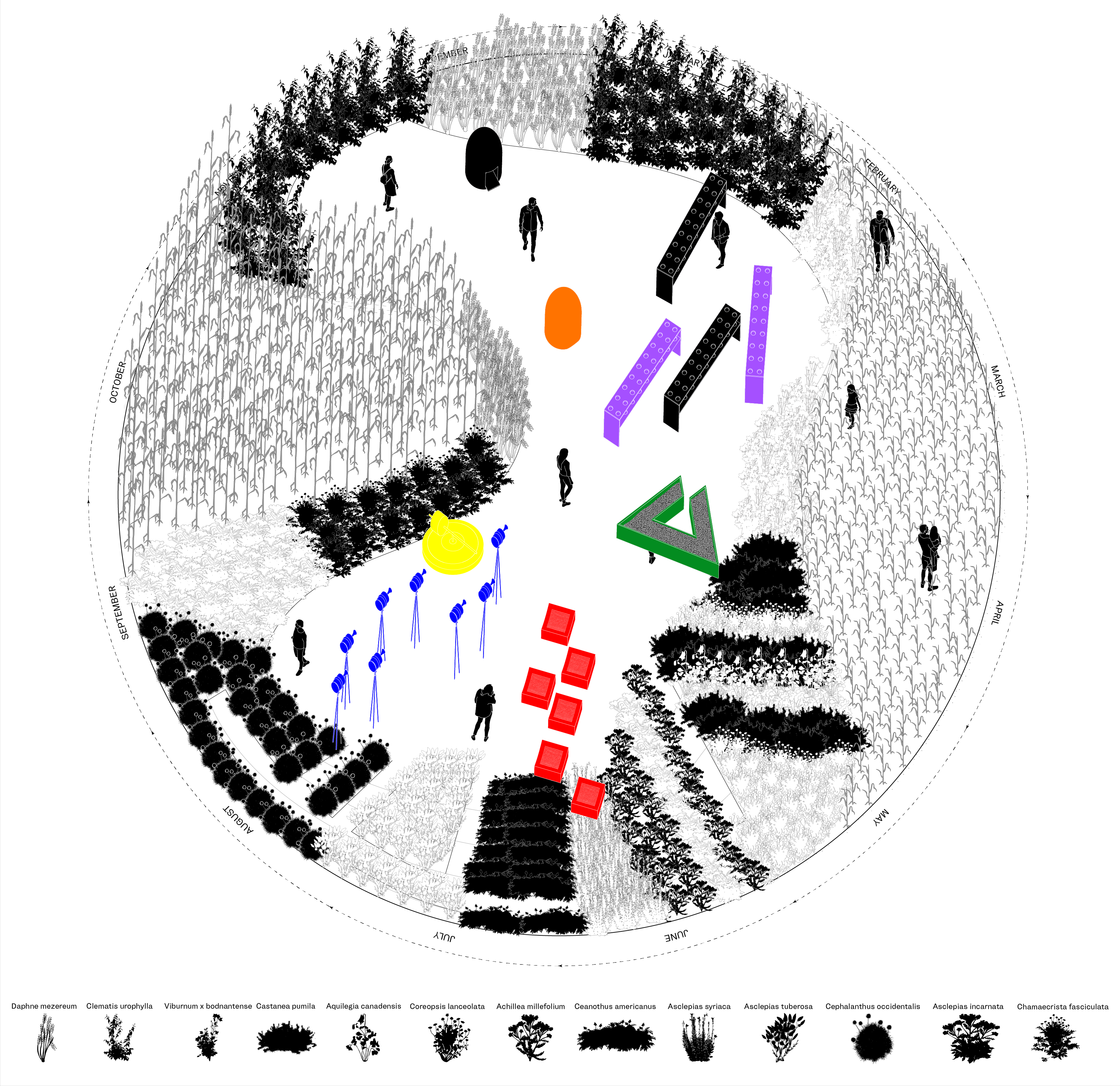

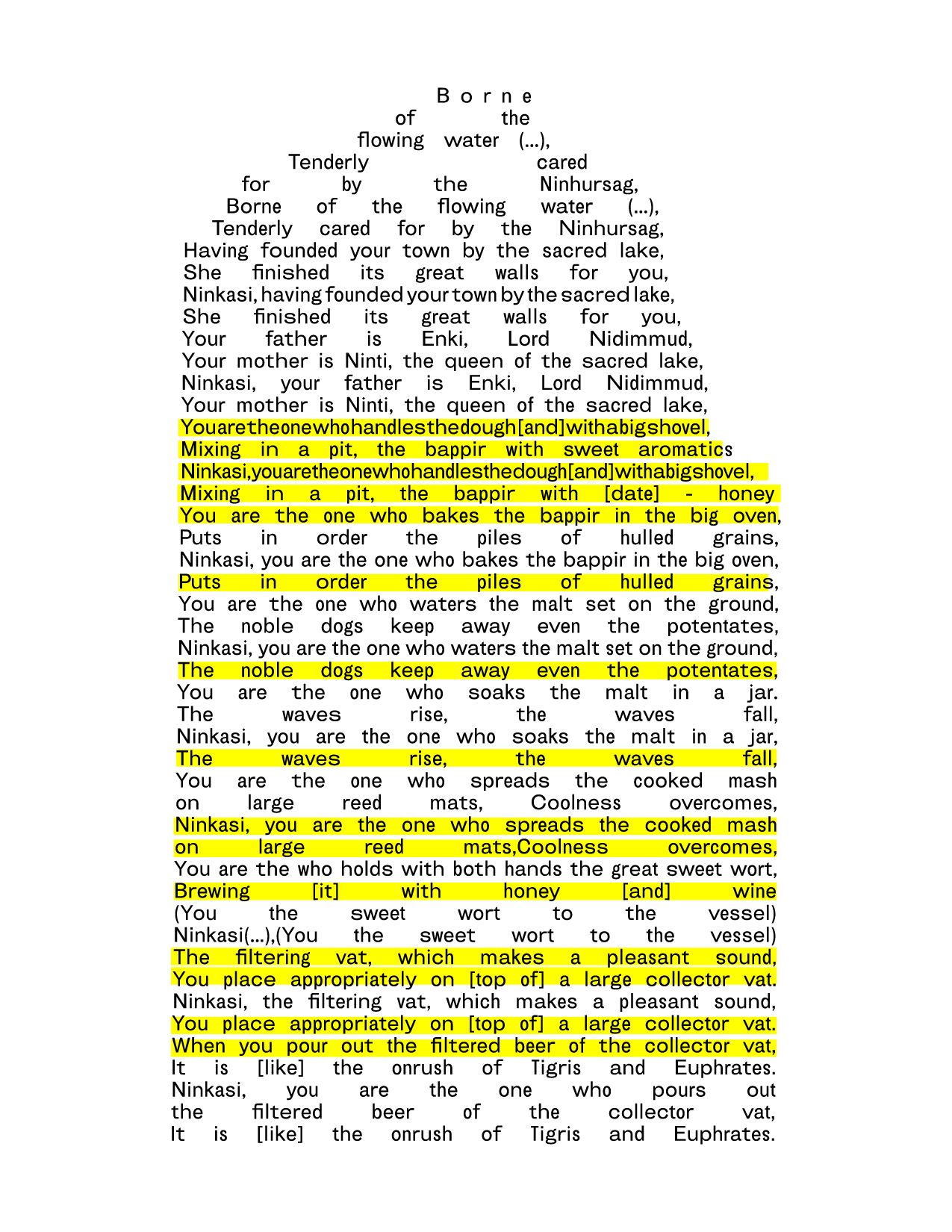

The «Hymn to Ninkasi» is a Sumerian poem dating to around 1800 BC, which according to translator Prince J. Dyneley, enacts a melodic ode to Ninkasi, the Sumerian goddess “who fills the mouth [with brew].” The ancient composition functioned as an audible guide for brewers, laying out the steps essential for the fermentation of Hordeum Vulgare, commonly known as cultivated barley.

Hordeum Vulgare, a member of the grass family and a major cereal grain grown in temperate regions worldwide, stands as one of the initial eight crops domesticated by Mesopotamian societies. In the annotations of Sumerian dctionaries, it becomes evident that raw barley alone did not fuel fermentation. Bappir, a Mesopotamian bread crafted from roasted germinated barley seeds played vital role. Although bappir served as a sustenance dring times of food scarcity, its primary purpose lay in the brewing process guided by Ninkasi.

The preparation of bappir was intrinsically linked to the natural rhythm of early summer barley harvests. Yet, for fermentation to happen, yeast requires a higher sugar content

than raw barley offers. This is where the alchemical property of sprouted barley, converting starch into sugars, becomes crucial. Once the seed germinates, the baby sprout begins producing amylase to break down the starch into a simpler sugar maltose, feeding its metabolism until it can photosynthesize its own food.

Through Bappir, bread of germinated barley seeds, the Sumerians coincidentally uncovered this innate capability of barley, enabling yeast to ferment it into the revered brew. Thus, the sacred connection of bappir with the Sumerian brewing finds its reason. In the «Hymn to Ninkasi», barley fermentation assumes the pivotal role in proving An anthropological thesis that brew, rather than bead, catalyzed the transition of nomadic tribes to settled agricultural practices, and birthing civilization. For the Sumerians, fermentation was an avenue to honor and communicate with Ninkasi, the goddess, who mixes bappir with honey, nurturing the malt on the ground, filtering the beverages, and providing sustenance to human society. The enduring enigma lies in discerning whether the sacred essence of the Sumerianritual resides in the final product (the brew) or the transformative process (fermentation) itself. Perhaps, it embodies both. For contemporary fermenters, it remains a ritual f

or inviting the “unknown” force, except that it might no longer be the divine, but an untamed collaboration between plants (and other sources of fermentable materials) and the

once-unseen microorganisms. Fermentation happens with or without human intervention

.

Illustrations